One of the most intriguing remnants of Swanson's quest is her appearance on The Steve Allen Show in 1957, singing what she hoped would be the opening number to the show. It's strange to see Swanson's Desmond erupt into song, even more strange to hear the tragic movie queen warble in a trilling soprano that seems better suited to Jeanette MacDonald. It's hard to say whether a singing Swanson would have been a success, but it's fun to imagine what her performance might have been like.

It's the weekend and you're desperate for a flick to watch with your sweetheart, your friends, or alone on the sofa with a tub of ice cream. Werth & Wise can help! Every Friday Werth & Wise will present some of cinema's best, worst, and strangest offerings so you'll always have a film to gab about.

Showing posts with label Billy Wilder. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Billy Wilder. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Silent Singing on Sunset

Recently Sam Staggs' book about Sunset Boulevard arrived in the Film Gab library, and among the many interesting tidbits about the film and its aftereffects is star Gloria Swanson's long held desire to recreate the role of fallen silent star Norma Desmond in a Broadway musical. According to Staggs, she spent thousands on lawyers' fees, promotions, and on the salary of her young composers Richard Stapley and Dickson Hughes, only to have the project fall apart long before it reached the Great White Way. (Of course Sunset Boulevard did reach Broadway many years later, but with an Andrew Lloyd Webber score.)

One of the most intriguing remnants of Swanson's quest is her appearance on The Steve Allen Show in 1957, singing what she hoped would be the opening number to the show. It's strange to see Swanson's Desmond erupt into song, even more strange to hear the tragic movie queen warble in a trilling soprano that seems better suited to Jeanette MacDonald. It's hard to say whether a singing Swanson would have been a success, but it's fun to imagine what her performance might have been like.

One of the most intriguing remnants of Swanson's quest is her appearance on The Steve Allen Show in 1957, singing what she hoped would be the opening number to the show. It's strange to see Swanson's Desmond erupt into song, even more strange to hear the tragic movie queen warble in a trilling soprano that seems better suited to Jeanette MacDonald. It's hard to say whether a singing Swanson would have been a success, but it's fun to imagine what her performance might have been like.

Friday, October 19, 2012

Escape from New York!

Wise: Hello, Werth.

Werth: Hi, Wise. What's with the mega-jumbo-latte and the Times' real estate section?

Wise: My insomnia has been acting up lately, and I've been fantasizing about a boondock cottage somewhere I can catch up on sleep.

Werth: One thing all New Yorkers have in common is the urge to sprint for the nearest railroad station to catch a train to our favorite out-of-town refuge whenever New York City life gets a little too... well, New York City.

Wise: Based on Peter Cameron's novel, The Weekend (1999) follows Lyle (David Conrad) as he and his new (and much younger) boyfriend Robert (James Duval) flee New York City for a quiet getaway at the upstate home of his old friends Marian and John (Deborah Kara Unger and Madmen's Jared Harris). Unfortunately, the weekend retreat turns out to be anything but quiet as long held frustrations, sorrows and resentments begin to surface, particularly Marion's complicated feelings for Lyle's deceased partner Tony (D.B. Sweeney).

Werth: She obviously watched The Cutting Edge one too many times.

Wise: Adding to the tumult is their glamorous but sharp-tonged neighbor Laura Ponti (Gena Rowlands), her snappish actress daughter Nina (Brooke Shields), and Nina's married lover Thierry (Gary Dourdan). Despite the large cast, the film is composed mostly of small scenes between pairs of characters, interspersed occasionally with blued-tinged flashbacks to Tony's past bons mots that feel something like an old Calvin Klein fragrance ad.

Werth: Don't you mean like an old Calvin Klein jeans ad?

Wise: I have to admit that I've avoided this film for over a decade because the novel it's based on is one of my favorites, and I was worried that Cameron's treasure box could only be butchered onscreen. And it turns out that I was only half right. Writer/director Brian Skeet has an instinctive feel for the rhythms of Cameron's prose, capturing the languorous feeling of the country after escaping the fetid heat of the city. If anything, he's perhaps too respectful of Cameron's words, cramming in entire passages of dialogue that feel spare within the expanse of a novel, but overblown on film.

Werth: Show it, don't say it, Skeet!

Wise: Still, Skeet gets a lot more more right than wrong. He is not slavishly faithful to his source, adapting and enriching the more cinematic parts of the book, eliding the rest. The cast is almost uniformly excellent, particularly Rowlands, who is at the center of the most lively scenes, and Unger, who manages to portray both her character's unlikability and her emotional frailty. Less successful is Sweeney who is forced to play more of a symbol than a character and whose Long Island inflection makes a stark contrast to Tony's platitudinousness while being posed like The Dying Gaul.

Werth: At the beginning of Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (1945) the main character is also packing for a trip to the country to get away from New York City. But Don Birnam (Ray Milland) quickly decides that instead of leaving by way of Metro North, he will take his usual escape route through a bottle of rye. You see, Don is a raging alcoholic.

Wise: Which is a lot cheaper than a house in the Hamptons.

Werth: Don handily ditches his well-meaning brother Wick (Phillip Terry, who at the time was spoused up with Joan Crawford) and his "best girl," the ritzy Helen St. James (the doe-eyed Jane Wyman wearing leopard courtesy of Edith Head) and begins a four day drinking binge that would put Mel Gibson to shame.

Before the film is done, Don is kicked out of his favorite bar, installed in a drunk tank, and roams up and down Third Avenue looking for a pawn shop that is open on Yom Kippur.

Wise: Clearly he should be taking the Day of atonement a bit more seriously.

Werth: Before its treacly ending, Lost Weekend is a disturbing look at how the mind of an alcoholic works—or doesn't work. Milland doesn't play for sympathy, his silky, gentlemanly demeanor turning into a web of disgusting lies, selfishness and criminality as he descends into a gin-fueled spiral. But because he's Ray Milland, we also can't bring ourselves to hate this jerk. He knows how pathetic he is, he is just powerless to stop himself from pursuing the next drink.

Wilder works his typical magic with story rather than a flashy cinematic style, but he does take the time to have fun with closeups on a booze-filled shot glass, water rings on the bar, and a DT fantasy with a bat and a mouse that is laughable until it's not.

The film made quite an impact when it was released—winning four Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor for Milland—but perhaps the most definitive proof of its popularity is that two years later the film was spoofed in the Bugs Bunny cartoon "Split Hare".

Wise: What's up, Drunk?

Werth: Whether you're packing your bags, or blacking out, join us next week for more Film Gab!

Werth: Hi, Wise. What's with the mega-jumbo-latte and the Times' real estate section?

Wise: My insomnia has been acting up lately, and I've been fantasizing about a boondock cottage somewhere I can catch up on sleep.

Werth: One thing all New Yorkers have in common is the urge to sprint for the nearest railroad station to catch a train to our favorite out-of-town refuge whenever New York City life gets a little too... well, New York City.

Wise: Based on Peter Cameron's novel, The Weekend (1999) follows Lyle (David Conrad) as he and his new (and much younger) boyfriend Robert (James Duval) flee New York City for a quiet getaway at the upstate home of his old friends Marian and John (Deborah Kara Unger and Madmen's Jared Harris). Unfortunately, the weekend retreat turns out to be anything but quiet as long held frustrations, sorrows and resentments begin to surface, particularly Marion's complicated feelings for Lyle's deceased partner Tony (D.B. Sweeney).

Werth: She obviously watched The Cutting Edge one too many times.

Wise: Adding to the tumult is their glamorous but sharp-tonged neighbor Laura Ponti (Gena Rowlands), her snappish actress daughter Nina (Brooke Shields), and Nina's married lover Thierry (Gary Dourdan). Despite the large cast, the film is composed mostly of small scenes between pairs of characters, interspersed occasionally with blued-tinged flashbacks to Tony's past bons mots that feel something like an old Calvin Klein fragrance ad.

Werth: Don't you mean like an old Calvin Klein jeans ad?

Wise: I have to admit that I've avoided this film for over a decade because the novel it's based on is one of my favorites, and I was worried that Cameron's treasure box could only be butchered onscreen. And it turns out that I was only half right. Writer/director Brian Skeet has an instinctive feel for the rhythms of Cameron's prose, capturing the languorous feeling of the country after escaping the fetid heat of the city. If anything, he's perhaps too respectful of Cameron's words, cramming in entire passages of dialogue that feel spare within the expanse of a novel, but overblown on film.

Werth: Show it, don't say it, Skeet!

Wise: Still, Skeet gets a lot more more right than wrong. He is not slavishly faithful to his source, adapting and enriching the more cinematic parts of the book, eliding the rest. The cast is almost uniformly excellent, particularly Rowlands, who is at the center of the most lively scenes, and Unger, who manages to portray both her character's unlikability and her emotional frailty. Less successful is Sweeney who is forced to play more of a symbol than a character and whose Long Island inflection makes a stark contrast to Tony's platitudinousness while being posed like The Dying Gaul.

Werth: At the beginning of Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (1945) the main character is also packing for a trip to the country to get away from New York City. But Don Birnam (Ray Milland) quickly decides that instead of leaving by way of Metro North, he will take his usual escape route through a bottle of rye. You see, Don is a raging alcoholic.

Wise: Which is a lot cheaper than a house in the Hamptons.

Werth: Don handily ditches his well-meaning brother Wick (Phillip Terry, who at the time was spoused up with Joan Crawford) and his "best girl," the ritzy Helen St. James (the doe-eyed Jane Wyman wearing leopard courtesy of Edith Head) and begins a four day drinking binge that would put Mel Gibson to shame.

Before the film is done, Don is kicked out of his favorite bar, installed in a drunk tank, and roams up and down Third Avenue looking for a pawn shop that is open on Yom Kippur.

Wise: Clearly he should be taking the Day of atonement a bit more seriously.

Werth: Before its treacly ending, Lost Weekend is a disturbing look at how the mind of an alcoholic works—or doesn't work. Milland doesn't play for sympathy, his silky, gentlemanly demeanor turning into a web of disgusting lies, selfishness and criminality as he descends into a gin-fueled spiral. But because he's Ray Milland, we also can't bring ourselves to hate this jerk. He knows how pathetic he is, he is just powerless to stop himself from pursuing the next drink.

Wilder works his typical magic with story rather than a flashy cinematic style, but he does take the time to have fun with closeups on a booze-filled shot glass, water rings on the bar, and a DT fantasy with a bat and a mouse that is laughable until it's not.

The film made quite an impact when it was released—winning four Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor for Milland—but perhaps the most definitive proof of its popularity is that two years later the film was spoofed in the Bugs Bunny cartoon "Split Hare".

Wise: What's up, Drunk?

Werth: Whether you're packing your bags, or blacking out, join us next week for more Film Gab!

Friday, June 15, 2012

Order in the Gab!

Wise: Hi there, Werth. Why the glum face?

Werth: Oh, hello, Wise. I've been doing jury duty all week and I'm bored, bored, bored.

Wise: Aren't you excited by fulfilling your civic duty?

Werth: I'd only be excited by my civic duty if it involved Christopher Meloni and the patented Dick Wolf sting.

Wise: Come on, Werth. It's your chance to participate in the wheels of justice. And, of course, it's the perfect opportunity to salute the pleasures of cinematic courtroom drama, like Billy Wilder's Witness for the Prosecution (1957). Adapted from Agatha Christie's West End hit dramatization of her own short story, Witness stars Charles Laughton as Sir Wilfrid Robarts, a brilliant English barrister just returned from a months-long stay in the hospital after a heart attack.

Famous for his unconventional tactics, Sir Wilfrid cannot resist—despite the strenuous objections of his nurse Miss Plimsoll (Laughton's real-life wife Elsa Lanchester)—when an intriguing case falls into his lap.

Werth: Thinking of Elsa and Charles together in flagrante makes me want to object.

Wise: Hapless veteran Leonard Vole (a very sweaty Tyrone Power) stands accused of murdering a rich spinster who had just made him the beneficiary of her will. His only alibi in the face of mounting circumstantial evidence is the testimony of his frigid German wife Christine (Marlene Dietrich).

Recognizing that Christine's chilly demeanor will only stymie his defense, Sir Wilfrid instead pokes holes in the prosecutor's theories and seems close to winning until Christine is called to testify against her husband. At the last minute, a mysterious phone call leads to evidence securing Leonard's exoneration, but it also raises Sir Wilfred's suspicions, culminating in a series of shocking reversals that theater owners warned viewers not to reveal.

Werth: The only mysterious phone call in my jury session was some old lady's marimba ringtone.

Wise: Part of Christie's genius is her ability to indulge in stereotypes as well as subvert them: Sir Wilfrid is both a blustering fool and a canny defender; Christine is both heartless and undone by her emotions. Wilder capitalizes on this by heightening both the drama and the campy-ness—even creating the role of the nurse to take advantage of Lanchester's chemistry with Laughton—making Witness probably the best film version of any Christie property.

Werth: Even better than Murder on the Orient Express?

Wise: Yes, because I think Witness really captures Christie's sense of humor. Her books feature some brutal crimes, but they're leavened by a certain tongue in cheek quality that the plummier adaptations of her work miss. For all its pleasures, Orient Express overindulges in nostalgia for 1930's Deco Britain, and misses the point (that Wilder so brilliantly captures) that Dame Agatha's idealized England is the conveyance for murderous hijinks and not the destination itself.

Werth: If you're in the mood for hijinks, no courtroom has more of them than the Tracy-Hepburn classic, Adam's Rib (1949). Adam (Tracy) and Amanda (Hepburn) are married lawyers who find themselves on the opposite sides of the table at an attempted murder trial. Adam wants to throw the book at ditzy, would-be murderess Doris Attinger (a sparkling Judy Holliday), but Amanda defends her, turning the trial into a crusade for women's equality.

Wise: I love when homicide transforms into urbane wit.

Werth: Written by married screenscribes Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, Adam's Rib mines the seemingly endless gold that the Tracy-Hepburn screen-teaming produced.Tracy is gruff and charming as a somewhat old-fashioned man who loves and respects his wife—but believes that the law is the law. Hepburn is regal in her defense of womanhood, but at the same time a giddy woman in love with her man.

The courtroom moves into the bedroom and vice versa as the two butt heads and soon these two legal eagle love birds are pecking each other's eyes out. The famous massage scene culminates with the heinie smack heard around the world.

Wise: The happy ending joke writes itself.

Werth: By the end we are less worried about who wins the case and more about how these two people who are made for each other will find their way back to a happy marriage. Tracy and Hepburn were so good at these battle of the sexes flicks because they gave their comedy a serious side.

If he was just a sexist pig and she an overheated women's libber, these movies would never work. But these two actors were so skilled at working their love and respect for each other into their characters that Adam and Amanda feel more full and real—making us see both sides and wanting to find a way for both of them to be right.

Director George Cukor also wisely enlisted the comic abilities of Holliday and fey-neighbor extraordinaire David Wayne to heighten the level of comedy in the picture without making Tracy and Hepburn shoulder all the humor. Many feel Adam's Rib is the best display of the Tracy and Hepburn magic, and this juror is happy to find in their favor.

Wise: So did your jury service end with you hooking up with Cher like Dennis Quaid did in Suspect (1987)?

Werth: Only the jury box knows for sure. Tune in next week for more legal shenanigans from Film Gab!

Werth: Oh, hello, Wise. I've been doing jury duty all week and I'm bored, bored, bored.

Wise: Aren't you excited by fulfilling your civic duty?

Werth: I'd only be excited by my civic duty if it involved Christopher Meloni and the patented Dick Wolf sting.

Wise: Come on, Werth. It's your chance to participate in the wheels of justice. And, of course, it's the perfect opportunity to salute the pleasures of cinematic courtroom drama, like Billy Wilder's Witness for the Prosecution (1957). Adapted from Agatha Christie's West End hit dramatization of her own short story, Witness stars Charles Laughton as Sir Wilfrid Robarts, a brilliant English barrister just returned from a months-long stay in the hospital after a heart attack.

Famous for his unconventional tactics, Sir Wilfrid cannot resist—despite the strenuous objections of his nurse Miss Plimsoll (Laughton's real-life wife Elsa Lanchester)—when an intriguing case falls into his lap.

Werth: Thinking of Elsa and Charles together in flagrante makes me want to object.

Wise: Hapless veteran Leonard Vole (a very sweaty Tyrone Power) stands accused of murdering a rich spinster who had just made him the beneficiary of her will. His only alibi in the face of mounting circumstantial evidence is the testimony of his frigid German wife Christine (Marlene Dietrich).

Recognizing that Christine's chilly demeanor will only stymie his defense, Sir Wilfrid instead pokes holes in the prosecutor's theories and seems close to winning until Christine is called to testify against her husband. At the last minute, a mysterious phone call leads to evidence securing Leonard's exoneration, but it also raises Sir Wilfred's suspicions, culminating in a series of shocking reversals that theater owners warned viewers not to reveal.

Werth: The only mysterious phone call in my jury session was some old lady's marimba ringtone.

Wise: Part of Christie's genius is her ability to indulge in stereotypes as well as subvert them: Sir Wilfrid is both a blustering fool and a canny defender; Christine is both heartless and undone by her emotions. Wilder capitalizes on this by heightening both the drama and the campy-ness—even creating the role of the nurse to take advantage of Lanchester's chemistry with Laughton—making Witness probably the best film version of any Christie property.

Werth: Even better than Murder on the Orient Express?

Wise: Yes, because I think Witness really captures Christie's sense of humor. Her books feature some brutal crimes, but they're leavened by a certain tongue in cheek quality that the plummier adaptations of her work miss. For all its pleasures, Orient Express overindulges in nostalgia for 1930's Deco Britain, and misses the point (that Wilder so brilliantly captures) that Dame Agatha's idealized England is the conveyance for murderous hijinks and not the destination itself.

Werth: If you're in the mood for hijinks, no courtroom has more of them than the Tracy-Hepburn classic, Adam's Rib (1949). Adam (Tracy) and Amanda (Hepburn) are married lawyers who find themselves on the opposite sides of the table at an attempted murder trial. Adam wants to throw the book at ditzy, would-be murderess Doris Attinger (a sparkling Judy Holliday), but Amanda defends her, turning the trial into a crusade for women's equality.

Wise: I love when homicide transforms into urbane wit.

Werth: Written by married screenscribes Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, Adam's Rib mines the seemingly endless gold that the Tracy-Hepburn screen-teaming produced.Tracy is gruff and charming as a somewhat old-fashioned man who loves and respects his wife—but believes that the law is the law. Hepburn is regal in her defense of womanhood, but at the same time a giddy woman in love with her man.

The courtroom moves into the bedroom and vice versa as the two butt heads and soon these two legal eagle love birds are pecking each other's eyes out. The famous massage scene culminates with the heinie smack heard around the world.

Wise: The happy ending joke writes itself.

Werth: By the end we are less worried about who wins the case and more about how these two people who are made for each other will find their way back to a happy marriage. Tracy and Hepburn were so good at these battle of the sexes flicks because they gave their comedy a serious side.

If he was just a sexist pig and she an overheated women's libber, these movies would never work. But these two actors were so skilled at working their love and respect for each other into their characters that Adam and Amanda feel more full and real—making us see both sides and wanting to find a way for both of them to be right.

Director George Cukor also wisely enlisted the comic abilities of Holliday and fey-neighbor extraordinaire David Wayne to heighten the level of comedy in the picture without making Tracy and Hepburn shoulder all the humor. Many feel Adam's Rib is the best display of the Tracy and Hepburn magic, and this juror is happy to find in their favor.

Wise: So did your jury service end with you hooking up with Cher like Dennis Quaid did in Suspect (1987)?

Werth: Only the jury box knows for sure. Tune in next week for more legal shenanigans from Film Gab!

Friday, June 1, 2012

Happy Birthday, MM!

Werth: Happy... Birthday... to youuuuuuuuu. Happy... Birthday—

Wise: Normally I wouldn't interrupt your introduction, but your breathy birthday song in a skintight spangled gown is making me feel funny... and not where the bathing suit goes.

Werth: I just couldn't think of a better way to wish Marilyn Monroe a happy 86th birthday than with her very own iconic 1962 birthday song to President Kennedy.

Wise: Perhaps a greeting card from Maxine would have sufficed.

Werth: I just get so excited about Marilyn. She was my entrée into the wonderful world of classic films and I'll always have a soft spot in my lil' ol' gay heart for her.

Wise: Right next to the soft spots reserved for Joan Crawford and dancing at the Pyramid.

Werth: I'll start off this double-barrel birthday salute to Marilyn with one of her comedies, Billy Wilder's The Seven Year Itch (1955). When goofy, dime-store novel editor Richard Sherman's (Tom Ewell) wife and son head to the country to escape the brutal NYC summer heat, Sherman and his fertile imagination are left to run wild. Before long he is opening his soda with the kitchen cabinet handle, smoking cigarettes and fantasizing in Cinemascope about all the women who just can't resist his animal magnetism.

Wise: Sounds like an evening at your house.

Werth: But when a new tenant (Monroe) buzzes his buzzer and gets her fan caught in the door, Sherman is flummoxed by a real-life fantasy that could make his summer even hotter.

Wise: Because nothing is hotter than the fish smell on Canal Street in July.

Werth: Marilyn is at the peak of her comedic talents here, crafting her dumb blonde character to be more than just a bubble-headed male sex fantasy. She may not know who Rachmaninoff is but she knows it's classical music, "because there's no vocal."

She brilliantly satirizes the commercial spokesmodel by explaining how she does her Dazzledent toothpaste ad noting, "...every time I show my teeth on television, I'm appearing before more people

than Sarah Bernhardt appeared before in her whole career. It's something to think about." Monroe even gets to enter Sherman's fantasies as a tricked-out Natahsa Fatale-esque temptress. Her monologue at the end of the film about what makes a man exciting flies in the face of her dumb blonde persona—and legend has it, it was done in one take.

Movie lore abounds about this film with my favorite story being the one about Marilyn's descent down the stairs in a nightie. Wilder ordered her to take her bra off, as it would be ridiculous for a girl to wear a bra under her nightie. Monroe insisted she wasn't wearing a bra, but Wilder refused to believe anyone's breasts could look that good without one. So Monroe grabbed Wilder's hand, put it under her nightie, and settled that argument.

Wise: She should have negotiated for the UN.

Werth: Marilyn exudes simple, sexual joy in Seven Year Itch, with the famous subway vent scene vaulting her already successful career into the Classic Hollywood stratosphere. It is an iconic scene that exemplifies the sort of sexy wit that makes Seven Year Itch a memorable comedy of the 1950's, and Marilyn the most memorable blonde of the 20th Century.

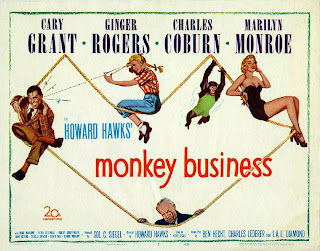

Wise: She wasn't quite so blonde—but no less memorable—in Monkey Business (1952), a Howard Hawks screwball comedy about scientist Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) searching for an elixir of youth and the hijinks that result when Barnaby and his wife (Ginger Rogers) keep getting doped up on the formula after one of the lab chimps dumps it into the water cooler.

Werth: My chimps pour vodka into the water cooler where I work.

Wise: Grant and Rogers are obviously having a lot of fun acting like teenagers while under the influence of the cocktail, but it's when they're playing adults that the sparks really fly. Grant does a variation on his befuddled-but-charming scientist routine—something he'd perfected in Bringing Up Baby—;

Rogers, however, is fuller and more womanly than when she was dancing with Fred Astaire. She'd always played a gal who could handle herself, but in this movie she acts as though she could handle her partner, too.

Werth: And a couple monkeys.

Wise: Hawks' pacing seems a bit off. While there are many delightful moments, the film never fully takes flight. Perhaps it's because the premise doesn't feel grounded in reality; or perhaps the anxieties of living in the atomic age make the possibility of eternal youth feel terrifyingly close at hand.

Werth: Don't forget to mention the Birthday Girl.

Wise: Whatever its faults, the film gives a captivating glance at an embryonic stage of the Monroe legend. Playing Miss Laurel, the knockout secretary to the head of the chemical company where Grant works, she naturally becomes the object of Grant's attention when he succumbs to the formula.

They go for a joyride in a hot rod, take in the afternoon at the pool, and spin around the roller rink—basically all her role required was a sexy jiggle—but Monroe invests her dumb blonde with a lot of smarts. Even in scenes where she's not the focus of the action, it's impossible not to watch her every move.

Werth: And pilfering attention from a charismatic screen legend like Grant is no piece of cake.

Wise: Speaking of cake, how about we indulge in a piece to celebrate Marilyn's birthday?

Werth: I'm afraid that might make this dress explode.

Wise: That's fine as long as we can reassemble all the pieces in time for next week's Film Gab.

Wise: Normally I wouldn't interrupt your introduction, but your breathy birthday song in a skintight spangled gown is making me feel funny... and not where the bathing suit goes.

Wise: Perhaps a greeting card from Maxine would have sufficed.

Werth: I just get so excited about Marilyn. She was my entrée into the wonderful world of classic films and I'll always have a soft spot in my lil' ol' gay heart for her.

Wise: Right next to the soft spots reserved for Joan Crawford and dancing at the Pyramid.

Werth: I'll start off this double-barrel birthday salute to Marilyn with one of her comedies, Billy Wilder's The Seven Year Itch (1955). When goofy, dime-store novel editor Richard Sherman's (Tom Ewell) wife and son head to the country to escape the brutal NYC summer heat, Sherman and his fertile imagination are left to run wild. Before long he is opening his soda with the kitchen cabinet handle, smoking cigarettes and fantasizing in Cinemascope about all the women who just can't resist his animal magnetism.

Wise: Sounds like an evening at your house.

Werth: But when a new tenant (Monroe) buzzes his buzzer and gets her fan caught in the door, Sherman is flummoxed by a real-life fantasy that could make his summer even hotter.

Wise: Because nothing is hotter than the fish smell on Canal Street in July.

Werth: Marilyn is at the peak of her comedic talents here, crafting her dumb blonde character to be more than just a bubble-headed male sex fantasy. She may not know who Rachmaninoff is but she knows it's classical music, "because there's no vocal."

She brilliantly satirizes the commercial spokesmodel by explaining how she does her Dazzledent toothpaste ad noting, "...every time I show my teeth on television, I'm appearing before more people

than Sarah Bernhardt appeared before in her whole career. It's something to think about." Monroe even gets to enter Sherman's fantasies as a tricked-out Natahsa Fatale-esque temptress. Her monologue at the end of the film about what makes a man exciting flies in the face of her dumb blonde persona—and legend has it, it was done in one take.

Movie lore abounds about this film with my favorite story being the one about Marilyn's descent down the stairs in a nightie. Wilder ordered her to take her bra off, as it would be ridiculous for a girl to wear a bra under her nightie. Monroe insisted she wasn't wearing a bra, but Wilder refused to believe anyone's breasts could look that good without one. So Monroe grabbed Wilder's hand, put it under her nightie, and settled that argument.

Wise: She should have negotiated for the UN.

Werth: Marilyn exudes simple, sexual joy in Seven Year Itch, with the famous subway vent scene vaulting her already successful career into the Classic Hollywood stratosphere. It is an iconic scene that exemplifies the sort of sexy wit that makes Seven Year Itch a memorable comedy of the 1950's, and Marilyn the most memorable blonde of the 20th Century.

Wise: She wasn't quite so blonde—but no less memorable—in Monkey Business (1952), a Howard Hawks screwball comedy about scientist Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) searching for an elixir of youth and the hijinks that result when Barnaby and his wife (Ginger Rogers) keep getting doped up on the formula after one of the lab chimps dumps it into the water cooler.

Werth: My chimps pour vodka into the water cooler where I work.

Wise: Grant and Rogers are obviously having a lot of fun acting like teenagers while under the influence of the cocktail, but it's when they're playing adults that the sparks really fly. Grant does a variation on his befuddled-but-charming scientist routine—something he'd perfected in Bringing Up Baby—;

Rogers, however, is fuller and more womanly than when she was dancing with Fred Astaire. She'd always played a gal who could handle herself, but in this movie she acts as though she could handle her partner, too.

Werth: And a couple monkeys.

Wise: Hawks' pacing seems a bit off. While there are many delightful moments, the film never fully takes flight. Perhaps it's because the premise doesn't feel grounded in reality; or perhaps the anxieties of living in the atomic age make the possibility of eternal youth feel terrifyingly close at hand.

Werth: Don't forget to mention the Birthday Girl.

Wise: Whatever its faults, the film gives a captivating glance at an embryonic stage of the Monroe legend. Playing Miss Laurel, the knockout secretary to the head of the chemical company where Grant works, she naturally becomes the object of Grant's attention when he succumbs to the formula.

They go for a joyride in a hot rod, take in the afternoon at the pool, and spin around the roller rink—basically all her role required was a sexy jiggle—but Monroe invests her dumb blonde with a lot of smarts. Even in scenes where she's not the focus of the action, it's impossible not to watch her every move.

Werth: And pilfering attention from a charismatic screen legend like Grant is no piece of cake.

Wise: Speaking of cake, how about we indulge in a piece to celebrate Marilyn's birthday?

Werth: I'm afraid that might make this dress explode.

Wise: That's fine as long as we can reassemble all the pieces in time for next week's Film Gab.

Friday, April 27, 2012

We Gab Hard for the Money

Werth: Hullo, Wise.

Werth: Work has been really busy of late. It's totally getting in the way of my watching old movies and scouring the internet for pictures I don't already have of Joan Crawford.

Wise: I'm sorry to hear that, but I can totally sympathize. Sometimes work feels like it's swallowing up the best of me and only leaving scraps behind.

Werth: You know what would make me feel much better?

Wise: Winning the lottery and being named Robert Osborn's successor?

Werth: Yes, but in the meantime I was hoping we could try some good ol' Hollywood escapism and gab about great movies where people's lives take an interesting turn because of their jobs.

Wise: You know I'm game. Cinema therapy is the great cure-all.

Werth: And nothing cures quite like a Billy Wilder comedy—although 1960's The Apartment would be better classified as a comedy/drama. C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is an employee of the massive Consolidated Life Company. Shown sitting at his desk in a cavernous, industrial-style common workroom whose lights and desks seem to stretch off into infinity, C.C. is already primed to move up the corporate ladder. To curry favor with his bosses, C.C. makes his W. 67th St. apartment available to his superiors as a destination for their clandestine quickies with women other than their wives.

Werth: Unfortunately for C.C., this means a lot of time spent loitering outside his building or walking in Central Park in the dead of night waiting for his bosses to finish with their floozies.

But it all appears to be worth it when the head of PR, Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray at his slickest) offers C.C. a promotion and his own office—provided Mr. Sheldrake can get in on the love nest action.

Wise: Wow, the absent-minded professor not only invented flubber, but was also a dog.

Werth: C.C. accepts, of course, and is anxious to share his promotion news with the elevator-girl of his dreams, Miss Kubelick (the recently turned 78 Shirley MacLaine). But what C.C. doesn't know is that Miss Kubelick is actually the chippie Mr. Sheldrake is having an affair with in C.C.'s apartment.

Wise: It makes sloppy seconds so much easier when the girl is already in your bedroom.

Werth: It gets even sloppier when Miss Kubelick finds out that she is merely the latest girl in a long string of receptionists and actuaries for Mr. Sheldrake, so she attempts suicide Christmas Eve in C.C.'s apartment.

Wise: Okay, what happened to the comedy?

Werth: That's what's so refreshing about this movie. In the hands of a director like Blake Edwards this would be a door-slamming sex farce. But in Wilder's hands, the comedy and drama weave together to form something that, while not real enough to be called "realistic," is tender enough to be human.

Both MacLaine and Lemmon are perfectly cast for this blend of loneliness and levity. MacLaine's typical kooky pluckiness is more reserved than usual—but still endearingly charming—hiding an inner sadness borne of broken trust.

And Lemmon's brilliance at finding comedy in the smallest of motions and moments is utilized to its fullest, giving his lonely C.C. depth, even while he is straining his spaghetti with a tennis racket.

Wise: I use my tennis racket as a cheese grater.

Werth: Nominated for 10 Academy Awards and winning five—including the biggie, Best Picture—The Apartment would be the last truly great film that Wilder would make. But in a career that included such classics as Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Some Like it Hot (1959), The Apartment is the epitome of Wilder's ability to make us laugh one moment and sniffle the next.

Wise: Witticisms and the workplace also combine perfectly in It (1927), a confection starring silent screen mega-star Clara Bow as Betty Lou Spence, a shop girl just bursting with "It."

Werth: I'm assuming you don't mean she dresses like a clown and kills people through the sewage system.

Wise: Of course not. It is based on a short story by Elinor Glyn who defined "It" as "That quality possessed by some which draws all others by its magnetic force," and Clara Bow had that in spades.

Propelled to Hollywood stardom by winning a nationwide Fame and Fortune contest, Bow became one of the defining faces of the silent era and It became one of her defining roles. The film has occasionally been dismissed as a Cinderella story, but Bow shows a lot more pluck and ambition than the stereotypical fairy tale princess.

She falls for her boss, Cyrus Waltham (a dreamy Antonio Moreno), the scion of Waltham's Department Store where she works. Realizing that he will never notice her as a salesgirl, she strikes up a friendship with Cyrus' best friend Monty (William Austin inhabiting the fey dandy role later perfected by Edward Everett Horton) and convinces him to escort her to the Ritz where she engineers a meeting with Cyrus and he promptly becomes smitten by her.

Werth: Now all I can think about is a delicious, buttery cracker...

Wise: She makes a wager that he won't recognize her the next time they meet, and the following day at the store, he does just that. When he realizes his mistake, he offers to make good on their bet, and she suggests a trip to Coney Island. After a happily romantic excursion, things turn sour when she rebuffs his aggressive advances, only to turn even worse when a tabloid reporter (a young Gary Cooper in a non-speaking role), two priggish social workers, and the baby of

Betty's unmarried roommate incite a mix-up that convinces Cyrus that she is nothing but a golddigger. Furious, Betty hatches a plan to make Cyrus fall in love with her despite what he thinks are her failings and to humiliate him when he proposes. Since this is a comedy, her scheme doesn't come off as she plans, but a roundelay of mistaken identities, comeuppance for snobs, and a yachting accident ensures a happy ending.

Werth: You used roundelay and comeuppance in the same sentence. Are you going for a double word score or something?

Wise: It's interesting to compare It with a lot of contemporary romantic comedies because most of snafus that fuel the plot in this kind of film stem from Betty's principles rather than the sniveling humiliations in, say, your typical Katherine Heigl film. Betty is never less than her most authentic (and rambunctious) self, and if she is reduced to tears near the end of the film, it's not because she's missed out on some idealized prince, but because she has failed to find her equal. And that's why this film feels so satisfying despite its age: Betty finds her happy ending because she's earned it, and not because a romantic golden goose plopped in her lap totally undeserved.

Werth: Sorry, Wise. I hate to stop you, but I gotta get back to work.

Wise: Just don't forget to punch the clock for next week's Film Gab.

Wise: Hi, Werth? What's wrong? You look like you're about to eat my brains.

Wise: I'm sorry to hear that, but I can totally sympathize. Sometimes work feels like it's swallowing up the best of me and only leaving scraps behind.

Werth: You know what would make me feel much better?

Wise: Winning the lottery and being named Robert Osborn's successor?

Werth: Yes, but in the meantime I was hoping we could try some good ol' Hollywood escapism and gab about great movies where people's lives take an interesting turn because of their jobs.

Wise: You know I'm game. Cinema therapy is the great cure-all.

Werth: And nothing cures quite like a Billy Wilder comedy—although 1960's The Apartment would be better classified as a comedy/drama. C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is an employee of the massive Consolidated Life Company. Shown sitting at his desk in a cavernous, industrial-style common workroom whose lights and desks seem to stretch off into infinity, C.C. is already primed to move up the corporate ladder. To curry favor with his bosses, C.C. makes his W. 67th St. apartment available to his superiors as a destination for their clandestine quickies with women other than their wives.

Wise: Poor wives. They never get the clandestine quickies.

Wise: Wow, the absent-minded professor not only invented flubber, but was also a dog.

Werth: C.C. accepts, of course, and is anxious to share his promotion news with the elevator-girl of his dreams, Miss Kubelick (the recently turned 78 Shirley MacLaine). But what C.C. doesn't know is that Miss Kubelick is actually the chippie Mr. Sheldrake is having an affair with in C.C.'s apartment.

Wise: It makes sloppy seconds so much easier when the girl is already in your bedroom.

Wise: Okay, what happened to the comedy?

Werth: That's what's so refreshing about this movie. In the hands of a director like Blake Edwards this would be a door-slamming sex farce. But in Wilder's hands, the comedy and drama weave together to form something that, while not real enough to be called "realistic," is tender enough to be human.

Both MacLaine and Lemmon are perfectly cast for this blend of loneliness and levity. MacLaine's typical kooky pluckiness is more reserved than usual—but still endearingly charming—hiding an inner sadness borne of broken trust.

And Lemmon's brilliance at finding comedy in the smallest of motions and moments is utilized to its fullest, giving his lonely C.C. depth, even while he is straining his spaghetti with a tennis racket.

Wise: I use my tennis racket as a cheese grater.

Werth: Nominated for 10 Academy Awards and winning five—including the biggie, Best Picture—The Apartment would be the last truly great film that Wilder would make. But in a career that included such classics as Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Some Like it Hot (1959), The Apartment is the epitome of Wilder's ability to make us laugh one moment and sniffle the next.

Wise: Witticisms and the workplace also combine perfectly in It (1927), a confection starring silent screen mega-star Clara Bow as Betty Lou Spence, a shop girl just bursting with "It."

Werth: I'm assuming you don't mean she dresses like a clown and kills people through the sewage system.

Wise: Of course not. It is based on a short story by Elinor Glyn who defined "It" as "That quality possessed by some which draws all others by its magnetic force," and Clara Bow had that in spades.

She falls for her boss, Cyrus Waltham (a dreamy Antonio Moreno), the scion of Waltham's Department Store where she works. Realizing that he will never notice her as a salesgirl, she strikes up a friendship with Cyrus' best friend Monty (William Austin inhabiting the fey dandy role later perfected by Edward Everett Horton) and convinces him to escort her to the Ritz where she engineers a meeting with Cyrus and he promptly becomes smitten by her.

Werth: Now all I can think about is a delicious, buttery cracker...

Wise: She makes a wager that he won't recognize her the next time they meet, and the following day at the store, he does just that. When he realizes his mistake, he offers to make good on their bet, and she suggests a trip to Coney Island. After a happily romantic excursion, things turn sour when she rebuffs his aggressive advances, only to turn even worse when a tabloid reporter (a young Gary Cooper in a non-speaking role), two priggish social workers, and the baby of

Betty's unmarried roommate incite a mix-up that convinces Cyrus that she is nothing but a golddigger. Furious, Betty hatches a plan to make Cyrus fall in love with her despite what he thinks are her failings and to humiliate him when he proposes. Since this is a comedy, her scheme doesn't come off as she plans, but a roundelay of mistaken identities, comeuppance for snobs, and a yachting accident ensures a happy ending.

Werth: You used roundelay and comeuppance in the same sentence. Are you going for a double word score or something?

Wise: It's interesting to compare It with a lot of contemporary romantic comedies because most of snafus that fuel the plot in this kind of film stem from Betty's principles rather than the sniveling humiliations in, say, your typical Katherine Heigl film. Betty is never less than her most authentic (and rambunctious) self, and if she is reduced to tears near the end of the film, it's not because she's missed out on some idealized prince, but because she has failed to find her equal. And that's why this film feels so satisfying despite its age: Betty finds her happy ending because she's earned it, and not because a romantic golden goose plopped in her lap totally undeserved.

Werth: Sorry, Wise. I hate to stop you, but I gotta get back to work.

Wise: Just don't forget to punch the clock for next week's Film Gab.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)