Stern's most famous sitting was with Marilyn Monroe mere months before her death, revealing the skin and the soul of the actress at a time when she was attempting to re-invent herself. Like many photographers, Stern lived in the shadows of his more famous subjects, but we here at Film Gab tip our hats to a man who excelled at making the gods and goddesses of Hollywood immortal.

It's the weekend and you're desperate for a flick to watch with your sweetheart, your friends, or alone on the sofa with a tub of ice cream. Werth & Wise can help! Every Friday Werth & Wise will present some of cinema's best, worst, and strangest offerings so you'll always have a film to gab about.

Showing posts with label Cary Grant. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Cary Grant. Show all posts

Thursday, June 27, 2013

The Big Screen in the Sky

Stern's most famous sitting was with Marilyn Monroe mere months before her death, revealing the skin and the soul of the actress at a time when she was attempting to re-invent herself. Like many photographers, Stern lived in the shadows of his more famous subjects, but we here at Film Gab tip our hats to a man who excelled at making the gods and goddesses of Hollywood immortal.

Friday, April 19, 2013

Cuckoo for Cukor!

Werth: Hello, Wise.

Wise: Hello, Werth. Still basking in the glow of our weekend movie marathon?

Werth: Yes, and my cranberry sparkly cocktail.

Wise: It was great fun to watch the American Masters documentary On Cukor (2000) as well as one of his masterworks, The Philadelphia Story starring his frequent collaborator and longtime friend Katharine Hepburn. Based on the Broadway smash by Philip Barry, the film opens with one of the most recognizable (and funny) scenes in all of screwball comedy.

Hepburn plays Tracy Samantha Lord, an imperious socialite from the Philadelphia Main Line, who divorces her first husband, playboy C.K. Dexter Haven (Grant), and chooses self-made man George Kittredge (John Howard) as her next fiancé. The nuptuals attract the attention of the tabloid press and with the help of Dexter, reporter Macauly Conner (Jimmy Stewart) and photographer Liz Imbrie (Ruth Hussey) finagle invitations under assumed names sparking a series of madcap adventures, revelations, and hijinks that eventually lead to happily ever after.

Werth: Don't forget the drunken shenanigans!

Wise: After rapidly ascending the Hollywood ladder in the mid-30's, Hepburn's star had been somewhat tarnished by a series of misfires and flops at the end of the decade, prompting theater owners to label her "box office poison." Hepburn retreated to the stage, found a hit in Barry's play, and with the help of then-sweetheart Howard Hughes, she purchased the film rights and brought the project back to MGM where she insisted that Cukor direct.

It turns out to have been a savvy decision because his guidance helped her forge a performance that embraced both her somewhat prickly image as well as her more tender, romantic side.

Werth: Not to mention directing Stewart to his only competitive Oscar win.

Wise: The rest of the cast is uniformly excellent. Grant deploys all his usual charms, although he mutes his performance with a tinge of sadness, marking him as a heel who has seen the error of his ways. Stewart also shows unsuspected facets of his personality, leavening his everyman quality with a romantic passion that makes him alluring to Tracy. Cukor's hand is everywhere evident in the finished film, coaxing greater nuance from his actors and allowing the camera to linger on their faces, bringing the film's drama and humor into greater focus.

Werth: I found it interesting that On Cukor neglected to mention the long relationship Cukor enjoyed with film queen Joan Crawford. Starting with his pinch-hitting direction of 1935's No More Ladies, Cukor would direct Crawford only four times, but his work with her on 1939's The Women helped catapault Crawford into a new phase of her career, and started a lifelong friendship.

Crawford credited Cukor with helping her give more depth to her roles, and the Cukor Effect is on full display in their 1941 collaboration, A Woman's Face. A re-make of a 1938 Swedish film that helped launched Ingrid Bergman's career, A Woman's Face begins in a Swedish courtroom where Anna Holm (Crawford) is on trial for murder.

Wise: Sounds like Mildred Pierce meets the Swedish Chef.

Werth: Witness testimonies kickstart the flashback where Anna meets spendy playboy Torsten Barring (Conrad Veidt) as he struggles to pay his check at her restaurant, a Hansel and Gretel-esque setting with Anna as the waiting witch. We also see a fantastic makeup job as shadows and Anna's turned head are undone and we discover that half of her face is horribly disfigured.

The scarring is repellant and made more dramatic by the fact that we can still see half of Crawford's legendary face—a constant reminder of the beauty that might have been. Shunned and mistreated all her life, Anna's soul is as disfigured as her face, so she makes a living as a blackmailer and falls in love with the no-good Torsten.

Wise: I guess absconding with sopranos to the basement of the Paris Opera House was out of the question.

Werth: During a blackmail touch gone wrong, Anna meets plastic surgeon Dr.Gustaf Segert (Melvyn Douglas) who decides to re-make Anna's face. Like a Pygmalion of the soul, Dr. Segert hopes that by restoring the beauty to Anna's face, he can restore the beauty to her conscience. But Anna is now torn between two men and herself. Crawford often played tough cookies who were bad because they'd been made that way. But in no other film is this theme given such graphic visual expression.

Anna is coarse, cold-blooded and, in one particular slapping scene, vicious. But we see the grisly reason why: Crawford's innate sense of "otherness" is given a physical reality, so when her face is returned to normal (if Crawford's unique features could ever be considered normal) Crawford gives a great performance struggling to undo the hard exterior she'd formed to protect herself and become a woman deserving of love.

Wise: If only Faye Dunaway had been half as successful in removing her horrifyingly deformed mask.

Werth: Cukor was not usually known for thrillers, but the melodrama in A Woman's Face winds up going in that direction. Cukor made the unique decision not to include underscoring in some of the tensest scenes, letting the environmental sounds of a waterfall and jangling sleighbells give an eeriness to the proceedings.

It's not entirely successful, but A Woman's Face is clearly a warm-up for Cukor who three years later would make one of the best psychological thrillers of the Forties, Gaslight.

Wise: We'll have to watch that one on our next Cukor Festival.

Werth: I'll get the cocktails ready. Film Gabbers, what director-focused film festival would you like to gab about?

Wise: Hello, Werth. Still basking in the glow of our weekend movie marathon?

Werth: Yes, and my cranberry sparkly cocktail.

Wise: It was great fun to watch the American Masters documentary On Cukor (2000) as well as one of his masterworks, The Philadelphia Story starring his frequent collaborator and longtime friend Katharine Hepburn. Based on the Broadway smash by Philip Barry, the film opens with one of the most recognizable (and funny) scenes in all of screwball comedy.

Werth: Don't forget the drunken shenanigans!

Wise: After rapidly ascending the Hollywood ladder in the mid-30's, Hepburn's star had been somewhat tarnished by a series of misfires and flops at the end of the decade, prompting theater owners to label her "box office poison." Hepburn retreated to the stage, found a hit in Barry's play, and with the help of then-sweetheart Howard Hughes, she purchased the film rights and brought the project back to MGM where she insisted that Cukor direct.

It turns out to have been a savvy decision because his guidance helped her forge a performance that embraced both her somewhat prickly image as well as her more tender, romantic side.

Werth: Not to mention directing Stewart to his only competitive Oscar win.

Wise: The rest of the cast is uniformly excellent. Grant deploys all his usual charms, although he mutes his performance with a tinge of sadness, marking him as a heel who has seen the error of his ways. Stewart also shows unsuspected facets of his personality, leavening his everyman quality with a romantic passion that makes him alluring to Tracy. Cukor's hand is everywhere evident in the finished film, coaxing greater nuance from his actors and allowing the camera to linger on their faces, bringing the film's drama and humor into greater focus.

Crawford credited Cukor with helping her give more depth to her roles, and the Cukor Effect is on full display in their 1941 collaboration, A Woman's Face. A re-make of a 1938 Swedish film that helped launched Ingrid Bergman's career, A Woman's Face begins in a Swedish courtroom where Anna Holm (Crawford) is on trial for murder.

Wise: Sounds like Mildred Pierce meets the Swedish Chef.

Werth: Witness testimonies kickstart the flashback where Anna meets spendy playboy Torsten Barring (Conrad Veidt) as he struggles to pay his check at her restaurant, a Hansel and Gretel-esque setting with Anna as the waiting witch. We also see a fantastic makeup job as shadows and Anna's turned head are undone and we discover that half of her face is horribly disfigured.

Wise: I guess absconding with sopranos to the basement of the Paris Opera House was out of the question.

Werth: During a blackmail touch gone wrong, Anna meets plastic surgeon Dr.Gustaf Segert (Melvyn Douglas) who decides to re-make Anna's face. Like a Pygmalion of the soul, Dr. Segert hopes that by restoring the beauty to Anna's face, he can restore the beauty to her conscience. But Anna is now torn between two men and herself. Crawford often played tough cookies who were bad because they'd been made that way. But in no other film is this theme given such graphic visual expression.

Wise: If only Faye Dunaway had been half as successful in removing her horrifyingly deformed mask.

Wise: We'll have to watch that one on our next Cukor Festival.

Werth: I'll get the cocktails ready. Film Gabbers, what director-focused film festival would you like to gab about?

Friday, March 22, 2013

Happy 100 Lew!

Wise: Welcome back, Werth!

Werth: Good to be back, Wise. I see you held down the fort with your in-depth review of the new Oz flick.

Wise: It had everything except Mila Kunis' viral BBC Radio interview.

Werth: Now that I'm back, I thought we could wish a happy 100th birthday to Hollywood agent icon Lew Wasserman.

Wise: He repped a Film Gab's who's who of stars: Bette Davis, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Stewart, Judy Garland, Henry Fonda, Myrna Loy, Ginger Rogers, Gregory Peck, Billy Wilder and Gene Kelly

Werth: Wasserman became just as famous as many of his clients when, in the 1950's as head of MCA, he helped change the film industry through the practice of film packaging where Wasserman would gather a roster of talent across the spectrum of film specialties (actors, directors, writers, production designers, costumers, you name it!) and then pitch them out on projects as a whole. Not only did this make certain that MCA made a lot of money, but it also kept production teams together, ensuring that these hit-making artisans worked on more than one movie together.

Wasserman's relationship with Alfred Hitchcock is a perfect example. With MCA since the early Fifties, Hitchcock had become a household commodity through his television show and hit movies, but in 1959, with Wasserman's help, he would make one of his most iconic and popular films, North by Northwest.

Wise: Spy capers were a lot more thrilling in the days before Google Maps.

Werth: From the Saul Bass opening with vivid animation and Bernard Herrmann's sprinting score, North by Northwest flies (pun intended.) Cary Grant is Roger Thornhill, a bachelor advertising exec who accidentally interrupts a page at the Oak Room in the old Plaza Hotel who is calling for George Kaplan. This one quirk of fate sets into motion a cross-country, mistaken identity, cat-and-mouse game between Thornhill and criminal mastermind Phillip Vandamm (James Mason).

It's a literal planes, trains and automobiles adventure as Thornhill attempts to find the elusive George Kaplan and clear his name before Vandamm or his nefarious "secretary" Leonard (performed with gay, jilted-lover relish by Martin Landau) snuff him out.

Wise: Fey henchmen love to snuff.

Werth: While riding the Twentieth Century train to Chicago, Thornhill winds up bunking with Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), a cold, mysterious Hitchcock blond if there ever was one. The chemistry between Grant and Marie Saint nearly burns the celluloid.

Their dinner scene on the train and subsequent makeout session is one of the sexiest bits in classic film that just barely goes under the censors' radars. It's that type of energy that whisks this film through its twists and turns with only small moments to stop and catch our breath and appreciate Grant's Foster Brooks imitation.

Wise: That makes me thirsty for a bourbon, a sports car and a cap gun.

Werth: Hitchcock puts the Vistavision film format to its most spectacular use, creating horizons and heights that fill the widescreen with a desolate Indiana cornfield and the top of Mount Rushmore.

The post-Vertigo use of technicolor is a shade less overt, but still the siennas, salmon pinks, blue greens, and reds punctuate settings and costumes, earning the film a Best Art Direction-Set Decoration Oscar nomination. Many of the sets start off as real exterior shots, but the cornfield, Mount Rushmore, and the U.N. all become meticulously crafted sets or dreamy matte paintings under Hitchcock's direction.

At the beginning of the film Thornhill says in advertising, "there is no such thing as a lie." In a Hitchock film, everything, from the blonde to the Vandamm house set on top of Mount Rushmore is one thrilling, cinematic lie.

Wise: There may not be quite so many lies in The Band Wagon (1953), but it does involve some fancy footwork from another of Wasserman's clients, Fred Astaire. Considered by many as one of the best musicals from old Hollywood, The Band Wagon casts Astaire as fading movie star Tony Hunter who absconds to New York where he hopes to revive his film career by starring in a Broadway show written by his old pals Lester and Lily Marton (Oscar Levant and Nanette Fabray). Hoping to make a sensation, the trio convinces Broadway wunderkind Jeffrey Cordova (Jack Buchanan) to direct the show; instead he transforms the Martons's madcap musical into a grim update of Faust.

Werth: I know when I think of Faust, I think of tap numbers.

Wise: Buchanan's one brilliant coup is casting ballet star Gabrielle Gerard (Cyd Charisse) as the female lead despite the reservations of her manager/boyfriend Paul Byrd (Thomas Mitchell). Beyond that, his grandiose ideas prove to be a flop, and the highly anticipated tryout in New Haven bombs so badly that all the financial backers flee the production. To save the show, Tony sells his art collection to fund an overhaul and ends up with both a Broadway smash and the girl.

Werth: The art market was very good in 1953.

Wise: Screenwriting team Betty Comden and Adolph Green have obvious fun spoofing their own reputations—Fabray and Levant brilliantly capture the team's sophistication and its neuroses—as well as director Vincente Minnelli in the over-the-top campiness of Buchanan.

Of course Minnelli brings his own signature use of color and deft camera moves to the mix, although he wisely allows Astaire's genius to take center stage. The sparks never really fly between

Astaire and Charisse, nevertheless Astaire's dancing is impossibly romantic whether with a shoeshine man (Leroy Daniels) in a Times Square penny arcade or with Charisse in a soundstage version of Central Park that's almost better than the real thing.

Werth: It's all thanks to the late, great Lew Wasserman—who was better at picking movies than he was at picking eyewear.

Wise: Check back with Film Gab next week for more of our favorite picks.

Werth: Good to be back, Wise. I see you held down the fort with your in-depth review of the new Oz flick.

Wise: It had everything except Mila Kunis' viral BBC Radio interview.

Werth: Now that I'm back, I thought we could wish a happy 100th birthday to Hollywood agent icon Lew Wasserman.

Wise: He repped a Film Gab's who's who of stars: Bette Davis, Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Stewart, Judy Garland, Henry Fonda, Myrna Loy, Ginger Rogers, Gregory Peck, Billy Wilder and Gene Kelly

Werth: Wasserman became just as famous as many of his clients when, in the 1950's as head of MCA, he helped change the film industry through the practice of film packaging where Wasserman would gather a roster of talent across the spectrum of film specialties (actors, directors, writers, production designers, costumers, you name it!) and then pitch them out on projects as a whole. Not only did this make certain that MCA made a lot of money, but it also kept production teams together, ensuring that these hit-making artisans worked on more than one movie together.

Wasserman's relationship with Alfred Hitchcock is a perfect example. With MCA since the early Fifties, Hitchcock had become a household commodity through his television show and hit movies, but in 1959, with Wasserman's help, he would make one of his most iconic and popular films, North by Northwest.

Wise: Spy capers were a lot more thrilling in the days before Google Maps.

Werth: From the Saul Bass opening with vivid animation and Bernard Herrmann's sprinting score, North by Northwest flies (pun intended.) Cary Grant is Roger Thornhill, a bachelor advertising exec who accidentally interrupts a page at the Oak Room in the old Plaza Hotel who is calling for George Kaplan. This one quirk of fate sets into motion a cross-country, mistaken identity, cat-and-mouse game between Thornhill and criminal mastermind Phillip Vandamm (James Mason).

It's a literal planes, trains and automobiles adventure as Thornhill attempts to find the elusive George Kaplan and clear his name before Vandamm or his nefarious "secretary" Leonard (performed with gay, jilted-lover relish by Martin Landau) snuff him out.

Wise: Fey henchmen love to snuff.

Werth: While riding the Twentieth Century train to Chicago, Thornhill winds up bunking with Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), a cold, mysterious Hitchcock blond if there ever was one. The chemistry between Grant and Marie Saint nearly burns the celluloid.

Their dinner scene on the train and subsequent makeout session is one of the sexiest bits in classic film that just barely goes under the censors' radars. It's that type of energy that whisks this film through its twists and turns with only small moments to stop and catch our breath and appreciate Grant's Foster Brooks imitation.

Wise: That makes me thirsty for a bourbon, a sports car and a cap gun.

Werth: Hitchcock puts the Vistavision film format to its most spectacular use, creating horizons and heights that fill the widescreen with a desolate Indiana cornfield and the top of Mount Rushmore.

The post-Vertigo use of technicolor is a shade less overt, but still the siennas, salmon pinks, blue greens, and reds punctuate settings and costumes, earning the film a Best Art Direction-Set Decoration Oscar nomination. Many of the sets start off as real exterior shots, but the cornfield, Mount Rushmore, and the U.N. all become meticulously crafted sets or dreamy matte paintings under Hitchcock's direction.

At the beginning of the film Thornhill says in advertising, "there is no such thing as a lie." In a Hitchock film, everything, from the blonde to the Vandamm house set on top of Mount Rushmore is one thrilling, cinematic lie.

Wise: There may not be quite so many lies in The Band Wagon (1953), but it does involve some fancy footwork from another of Wasserman's clients, Fred Astaire. Considered by many as one of the best musicals from old Hollywood, The Band Wagon casts Astaire as fading movie star Tony Hunter who absconds to New York where he hopes to revive his film career by starring in a Broadway show written by his old pals Lester and Lily Marton (Oscar Levant and Nanette Fabray). Hoping to make a sensation, the trio convinces Broadway wunderkind Jeffrey Cordova (Jack Buchanan) to direct the show; instead he transforms the Martons's madcap musical into a grim update of Faust.

Werth: I know when I think of Faust, I think of tap numbers.

Wise: Buchanan's one brilliant coup is casting ballet star Gabrielle Gerard (Cyd Charisse) as the female lead despite the reservations of her manager/boyfriend Paul Byrd (Thomas Mitchell). Beyond that, his grandiose ideas prove to be a flop, and the highly anticipated tryout in New Haven bombs so badly that all the financial backers flee the production. To save the show, Tony sells his art collection to fund an overhaul and ends up with both a Broadway smash and the girl.

Werth: The art market was very good in 1953.

Wise: Screenwriting team Betty Comden and Adolph Green have obvious fun spoofing their own reputations—Fabray and Levant brilliantly capture the team's sophistication and its neuroses—as well as director Vincente Minnelli in the over-the-top campiness of Buchanan.

Of course Minnelli brings his own signature use of color and deft camera moves to the mix, although he wisely allows Astaire's genius to take center stage. The sparks never really fly between

Astaire and Charisse, nevertheless Astaire's dancing is impossibly romantic whether with a shoeshine man (Leroy Daniels) in a Times Square penny arcade or with Charisse in a soundstage version of Central Park that's almost better than the real thing.

Werth: It's all thanks to the late, great Lew Wasserman—who was better at picking movies than he was at picking eyewear.

Wise: Check back with Film Gab next week for more of our favorite picks.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Happy 109th, Archie Leach!

Wise: Werth!

Werth: With all the cake from our recent birthday salutes, I'm busting out of my pants.

Wise: Cake just wants you to be happy. It's the pants that double-crossed you.

Werth: Today is really a special birthday, though, as it would have been Hollwood icon Cary Grant's 109th birthday.

Wise: Which means that Taylor Swift is just a bit too old to be his co-star.

Werth: In his later years, Hollywood did have a habit of making Grant the romantic partner for some much younger leading ladies. But in the 1940 classic His Girl Friday, Grant was evenly matched age- and acting-wise with the fast-talking Rosalind Russell. Grant is Walter Burns, a sly, underhanded newspaper editor who is willing to do anything to break the story. Russell is Hildy, his recent ex-wife who stops by the office to let him know she's not only quitting his rag,

but she's engaged to be married to insurance salesman Bruce Baldwin who "looks like Ralph Bellamy" (a punchline paid off by the fact that Bruce is played by Ralph Bellamy).

Wise: Making him prince of the second banana role.

Werth: Walter refuses to lose his best reporter and his wife, so he concocts a plan to trick Hildy into helping with one last story hoping she'll miss her train to Albany and a "normal" life. Walter's plan is helped along by the fact that a controversial execution is about to take place and Hildy can't resist covering it.

Howard Hawks directed His Girl Friday at a breakneck pace with the comic zingers, sly glances, and even the stripes on Hildy's hat and coat zipping by so fast that we have to lean forward to catch every wonderful moment. It's the perfect pacing for a story about journalism, racing across the screen like an AP newsflash.

Wise: Although at the time, it must have been the teletype machine.

Wise: Grant plays an equally appealing, although more sinister, character in Suspicion (1941). As irresponsible playboy Johnnie Aysgarth, Grant stumbles into the train compartment of bookish Lena McLaidlaw (Joan Fontaine) and promptly scams her for first class fare before gradually falling for her.

After a whirlwind romance, the pair elope, much to the disapproval of Lena's staid—and wealthy—parents. After they return from a grand honeymoon, Lena begins to realize that Johnnie's finances are a tangle of debts, promises, and lost bets at the racetrack. This being an Alfred Hitchcock film, she also begins to suspect that her beloved husband has a darker side.

Wise: As Johnnie's financial troubles mount, she begins to wonder to what lengths he'll go to shore up his failed business ventures. And when his best pal—and erstwhile business partner—turns up in Paris dead under mysterious circumstances, she begins to fear for her life.

Wise: Fontaine won the Academy Award for this, her second outing with Hitchcock (she was also nominated for her first, Rebecca, the year before), and her evolution—from a dowdy spinster to a woman possessed by lust and finally to a prisoner of her own fears—unfolds thrillingly, yet believably.

Of course Grant's performance provides the perfect support: his charm could just as easily melt an old maid's frozen heart as it could drain the lifeblood from her veins. But as a pair, the two make one of Hitchcock's most erotic screen couples. Grant's roguishness barely conceals his carnal desires, while Fontaine's slightly breathless performance makes audiences wonder if she might willingly sacrifice her life to her husband's gambling addiction in exchange for just one more roll in the sack.

Werth: Speaking of sacks, I need something to wear that has a little more give than these pants.

Wise: Just have another piece of cake and we'll both wear muumuus for next week's Film Gab.

Friday, June 1, 2012

Happy Birthday, MM!

Werth: Happy... Birthday... to youuuuuuuuu. Happy... Birthday—

Wise: Normally I wouldn't interrupt your introduction, but your breathy birthday song in a skintight spangled gown is making me feel funny... and not where the bathing suit goes.

Werth: I just couldn't think of a better way to wish Marilyn Monroe a happy 86th birthday than with her very own iconic 1962 birthday song to President Kennedy.

Wise: Perhaps a greeting card from Maxine would have sufficed.

Werth: I just get so excited about Marilyn. She was my entrée into the wonderful world of classic films and I'll always have a soft spot in my lil' ol' gay heart for her.

Wise: Right next to the soft spots reserved for Joan Crawford and dancing at the Pyramid.

Werth: I'll start off this double-barrel birthday salute to Marilyn with one of her comedies, Billy Wilder's The Seven Year Itch (1955). When goofy, dime-store novel editor Richard Sherman's (Tom Ewell) wife and son head to the country to escape the brutal NYC summer heat, Sherman and his fertile imagination are left to run wild. Before long he is opening his soda with the kitchen cabinet handle, smoking cigarettes and fantasizing in Cinemascope about all the women who just can't resist his animal magnetism.

Wise: Sounds like an evening at your house.

Werth: But when a new tenant (Monroe) buzzes his buzzer and gets her fan caught in the door, Sherman is flummoxed by a real-life fantasy that could make his summer even hotter.

Wise: Because nothing is hotter than the fish smell on Canal Street in July.

Werth: Marilyn is at the peak of her comedic talents here, crafting her dumb blonde character to be more than just a bubble-headed male sex fantasy. She may not know who Rachmaninoff is but she knows it's classical music, "because there's no vocal."

She brilliantly satirizes the commercial spokesmodel by explaining how she does her Dazzledent toothpaste ad noting, "...every time I show my teeth on television, I'm appearing before more people

than Sarah Bernhardt appeared before in her whole career. It's something to think about." Monroe even gets to enter Sherman's fantasies as a tricked-out Natahsa Fatale-esque temptress. Her monologue at the end of the film about what makes a man exciting flies in the face of her dumb blonde persona—and legend has it, it was done in one take.

Movie lore abounds about this film with my favorite story being the one about Marilyn's descent down the stairs in a nightie. Wilder ordered her to take her bra off, as it would be ridiculous for a girl to wear a bra under her nightie. Monroe insisted she wasn't wearing a bra, but Wilder refused to believe anyone's breasts could look that good without one. So Monroe grabbed Wilder's hand, put it under her nightie, and settled that argument.

Wise: She should have negotiated for the UN.

Werth: Marilyn exudes simple, sexual joy in Seven Year Itch, with the famous subway vent scene vaulting her already successful career into the Classic Hollywood stratosphere. It is an iconic scene that exemplifies the sort of sexy wit that makes Seven Year Itch a memorable comedy of the 1950's, and Marilyn the most memorable blonde of the 20th Century.

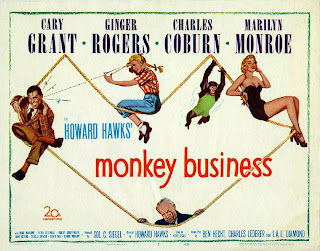

Wise: She wasn't quite so blonde—but no less memorable—in Monkey Business (1952), a Howard Hawks screwball comedy about scientist Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) searching for an elixir of youth and the hijinks that result when Barnaby and his wife (Ginger Rogers) keep getting doped up on the formula after one of the lab chimps dumps it into the water cooler.

Werth: My chimps pour vodka into the water cooler where I work.

Wise: Grant and Rogers are obviously having a lot of fun acting like teenagers while under the influence of the cocktail, but it's when they're playing adults that the sparks really fly. Grant does a variation on his befuddled-but-charming scientist routine—something he'd perfected in Bringing Up Baby—;

Rogers, however, is fuller and more womanly than when she was dancing with Fred Astaire. She'd always played a gal who could handle herself, but in this movie she acts as though she could handle her partner, too.

Werth: And a couple monkeys.

Wise: Hawks' pacing seems a bit off. While there are many delightful moments, the film never fully takes flight. Perhaps it's because the premise doesn't feel grounded in reality; or perhaps the anxieties of living in the atomic age make the possibility of eternal youth feel terrifyingly close at hand.

Werth: Don't forget to mention the Birthday Girl.

Wise: Whatever its faults, the film gives a captivating glance at an embryonic stage of the Monroe legend. Playing Miss Laurel, the knockout secretary to the head of the chemical company where Grant works, she naturally becomes the object of Grant's attention when he succumbs to the formula.

They go for a joyride in a hot rod, take in the afternoon at the pool, and spin around the roller rink—basically all her role required was a sexy jiggle—but Monroe invests her dumb blonde with a lot of smarts. Even in scenes where she's not the focus of the action, it's impossible not to watch her every move.

Werth: And pilfering attention from a charismatic screen legend like Grant is no piece of cake.

Wise: Speaking of cake, how about we indulge in a piece to celebrate Marilyn's birthday?

Werth: I'm afraid that might make this dress explode.

Wise: That's fine as long as we can reassemble all the pieces in time for next week's Film Gab.

Wise: Normally I wouldn't interrupt your introduction, but your breathy birthday song in a skintight spangled gown is making me feel funny... and not where the bathing suit goes.

Wise: Perhaps a greeting card from Maxine would have sufficed.

Werth: I just get so excited about Marilyn. She was my entrée into the wonderful world of classic films and I'll always have a soft spot in my lil' ol' gay heart for her.

Wise: Right next to the soft spots reserved for Joan Crawford and dancing at the Pyramid.

Werth: I'll start off this double-barrel birthday salute to Marilyn with one of her comedies, Billy Wilder's The Seven Year Itch (1955). When goofy, dime-store novel editor Richard Sherman's (Tom Ewell) wife and son head to the country to escape the brutal NYC summer heat, Sherman and his fertile imagination are left to run wild. Before long he is opening his soda with the kitchen cabinet handle, smoking cigarettes and fantasizing in Cinemascope about all the women who just can't resist his animal magnetism.

Wise: Sounds like an evening at your house.

Werth: But when a new tenant (Monroe) buzzes his buzzer and gets her fan caught in the door, Sherman is flummoxed by a real-life fantasy that could make his summer even hotter.

Wise: Because nothing is hotter than the fish smell on Canal Street in July.

Werth: Marilyn is at the peak of her comedic talents here, crafting her dumb blonde character to be more than just a bubble-headed male sex fantasy. She may not know who Rachmaninoff is but she knows it's classical music, "because there's no vocal."

She brilliantly satirizes the commercial spokesmodel by explaining how she does her Dazzledent toothpaste ad noting, "...every time I show my teeth on television, I'm appearing before more people

than Sarah Bernhardt appeared before in her whole career. It's something to think about." Monroe even gets to enter Sherman's fantasies as a tricked-out Natahsa Fatale-esque temptress. Her monologue at the end of the film about what makes a man exciting flies in the face of her dumb blonde persona—and legend has it, it was done in one take.

Movie lore abounds about this film with my favorite story being the one about Marilyn's descent down the stairs in a nightie. Wilder ordered her to take her bra off, as it would be ridiculous for a girl to wear a bra under her nightie. Monroe insisted she wasn't wearing a bra, but Wilder refused to believe anyone's breasts could look that good without one. So Monroe grabbed Wilder's hand, put it under her nightie, and settled that argument.

Wise: She should have negotiated for the UN.

Werth: Marilyn exudes simple, sexual joy in Seven Year Itch, with the famous subway vent scene vaulting her already successful career into the Classic Hollywood stratosphere. It is an iconic scene that exemplifies the sort of sexy wit that makes Seven Year Itch a memorable comedy of the 1950's, and Marilyn the most memorable blonde of the 20th Century.

Wise: She wasn't quite so blonde—but no less memorable—in Monkey Business (1952), a Howard Hawks screwball comedy about scientist Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) searching for an elixir of youth and the hijinks that result when Barnaby and his wife (Ginger Rogers) keep getting doped up on the formula after one of the lab chimps dumps it into the water cooler.

Werth: My chimps pour vodka into the water cooler where I work.

Wise: Grant and Rogers are obviously having a lot of fun acting like teenagers while under the influence of the cocktail, but it's when they're playing adults that the sparks really fly. Grant does a variation on his befuddled-but-charming scientist routine—something he'd perfected in Bringing Up Baby—;

Rogers, however, is fuller and more womanly than when she was dancing with Fred Astaire. She'd always played a gal who could handle herself, but in this movie she acts as though she could handle her partner, too.

Werth: And a couple monkeys.

Wise: Hawks' pacing seems a bit off. While there are many delightful moments, the film never fully takes flight. Perhaps it's because the premise doesn't feel grounded in reality; or perhaps the anxieties of living in the atomic age make the possibility of eternal youth feel terrifyingly close at hand.

Werth: Don't forget to mention the Birthday Girl.

Wise: Whatever its faults, the film gives a captivating glance at an embryonic stage of the Monroe legend. Playing Miss Laurel, the knockout secretary to the head of the chemical company where Grant works, she naturally becomes the object of Grant's attention when he succumbs to the formula.

They go for a joyride in a hot rod, take in the afternoon at the pool, and spin around the roller rink—basically all her role required was a sexy jiggle—but Monroe invests her dumb blonde with a lot of smarts. Even in scenes where she's not the focus of the action, it's impossible not to watch her every move.

Werth: And pilfering attention from a charismatic screen legend like Grant is no piece of cake.

Wise: Speaking of cake, how about we indulge in a piece to celebrate Marilyn's birthday?

Werth: I'm afraid that might make this dress explode.

Wise: That's fine as long as we can reassemble all the pieces in time for next week's Film Gab.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

---Cary-Grant,-Joan-Fontaine-791379.jpg)